|

Referring to the fact that Britain's two 1,000-foot superliners each could transport an infantry division at speeds over 30 knots, Winston Churchill credited Cunard Line's Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth with shortening World War II by a year. Viewed in this light, the magnitude of the loss of a third such ship, the French Line's superliner Normandie, in New York Harbor before she could transport a single soldier becomes clear.

In the 1920s, the European powers were vigorously competing to dominate the transatlantic passenger market. When Germany and Italy introduced modern high speed ships such as the Breman and the Rex, the pre-World War I passenger fleets of Britain and France were rendered obsolete. It was time for a leap forward -- the superliner. Britain was the first to begin construction on a 1,000-foot high speed behemoth. However when the Depression struck, work on the Queen Mary halted for more than 2 years. Consequently, the French answer to the Cunarder begun about a year after the British ship, was the first superliner to be completed. Normandie made her maiden voyage in 1935. While Queen Mary has been criticized as being a larger version of the pre-World War I Aquatania, Normandie was a revolution in design with streamlined decks free of ventilators and other clutter. Although never as popular as Queen Mary, Normandie and her British rival traded the North Atlantic speed record throughout the 1930s.. When war broke out in Europe in September 1939, both ships were in New York. Rather than risk submarine and air attacks. their owners decided to leave them in the neutral port. In March 1940, they were joined by the newly completed Queen Elizabeth and the three giants lay all but deserted at the piers that now comprise the Passenger Ship Terminal. Eventually, the British decided to put their ships to use and Normndie was left alone. Her fate was unclear as both the Free French and the Vichy government claimed her. Inasmuch as the Vichy government was now the government of France, it probably had the better claim to Normandie. However, giving the ship to Vichy would have been to give the valuable ship to the Nazis so the Roosevelt Administration was in no hurry to decide the issue. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Germany declared war on the United States. The U.S. Government quickly decided that Normandie should belong to America. It seized the ship and she was given to the U.S. Navy. Renamed USS Lafayette, work began to turn her into a troop ship. Normandie was renown for her elaborate art deco interiors. While a burner was attempting to remove one of the decorations in the Grand Salon, sparks from his torch ignited a pile of kapok life vests that had been left nearby. The fire quickly spread through the ship. Attempts to put out the fire were a comedy of errors. For example, most of Normandie's fire hoses had been removed from the ship and replaced with standard Navy-issue fire hoses. No one had considered that the Navy hoses might not be able to connect to Normandie's French metric system pipes. VladimirYorkevitch, the designer of the ship, happened to be in New York. He went to Pier 88 and after explaining who he was, Yorkevitch was taken to see the naval officer in charge. Normandie's designer attempted to persuade the officer to open Normandie's seacocks thereby allowing the ship to settle a few feet to the bottom in an upright position. Once the fire was out, the water could be easily pumped out of the lower decks, the ship would float and there would be little damage. |

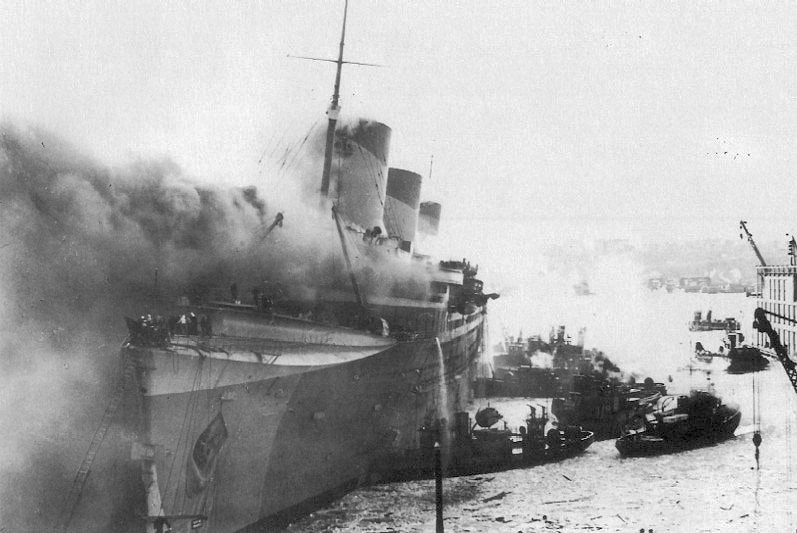

Above: Normandie on fire.

Below: Normandie capsized. The officer ignored Yorkevitch's advice. This was a high-profile event as thousands of people had thronged to see the fire. In any event, the situation was well in hand. A battery of fireboats and several fire engines were pouring tons of water onto Normandie and that would take care of the problem. Indeed, as the afternoon wore on the fire was put out and all appeared well except for the ship's distinct list.

Appearances were deceiving. All of the water that had been poured on the fire had made the ship top heavy. Pier 88 had had to be lengthened to accommodate the 1,000-foot superliners. To do this, the City had cut into the shore line of Manhattan island. This required cutting away rock and the City only removed what was necessary. As a result, there was a rock shelf under the water at the landward side of the berth. Normally, it did not come into play when the pier was in use. However, with the tide out, Normandie's bow came to rest against the rock shelf. This had the effect of stopping the ship from listing further even though she was now top heavy with all of the water that had been poured on her upper decks. That evening, the tide returned. Normandie rose along with the tide so that she was no longer being supported by the rock shelf. One-by-one the lines holding her to the pier snapped and the giant rolled over on her port side. What had appeared to be a close-call triumph was now an embarrassing disaster. A fence was hastily erected around the berth to hide the scene from onlookers. However, this was to little avail as the capsized ship could still be seen from New York' tall buildings. Normandie was too valuable not to salvage. Plans were drawn for turning her into an aircraft carrier after she was re-floated. Accordingly, the superstructure was cut away, the hull sealed and pumped out, The ship was righted. However, it took a long time to do this as much of this work had to be done by Navy divers working in near zero visibility often in near freezing water. By the time the work was finished in the fall of 1943, it no longer made sense to rebuild or to use the hull as the foundation for an aircraft carrier. American industry had been fully harnessed and it was now easier and less expensive to build new ships rather than convert the old liner. Normandie was towed to Brooklyn and then, in November 1946. to Port Newark where she was scrapped. |

|

|

|

Feature article - - historic ship (French Line) - - SS Normandie - - The End of the Normandie